Overcoming Our Hidden Biases

/THOUGHT PIECE BY IZZY CHAN

On days like this.

I read the morning/mourning news.

Hard to catch my breath.

Take-a-deep-breath.

I look over my children—especially my boy.

I ask myself, “Is today the day I have to break his heart with the whole truth?”

Do I have to tell him today all of what’s behind my panicked face and shrill voice when, on a hot summer day, he follows his friends outside the door into the world with a squirt gun in his hand?

When I take it away, how fully do I have to answer his complaint of “It’s NOT FAIR—why don’t you let me when his parents let him?”

Do I shatter him today? Or let him be a care-free child? Do I let just a little truth seep out? Do I lie?

“Come here sweetie. Look me in the eye. Your Dad and I love you so much. Can I have a hug?”

I hold him close and measure his height against my body. Head now is up to my second rib.

Only a little bit of truth today. Big truth when he reaches my shoulder?

I bend down to give kiss him on the forehead and give a bag of water balloons I found in the drawer.

Smile on his face, he bounds out the door.

I watch him play and I am all mixed up. Joy, fear and doubt. Hurts to know I don’t know how to protect him.

~ Amy, mother

As a documentary film that is fundamentally about challenging bias, we cannot be quiet during this time of public outrage over race and injustice. But much as we want to add our voice to the outrage, we also want to start a meaningful conversation about what we can do to change this.

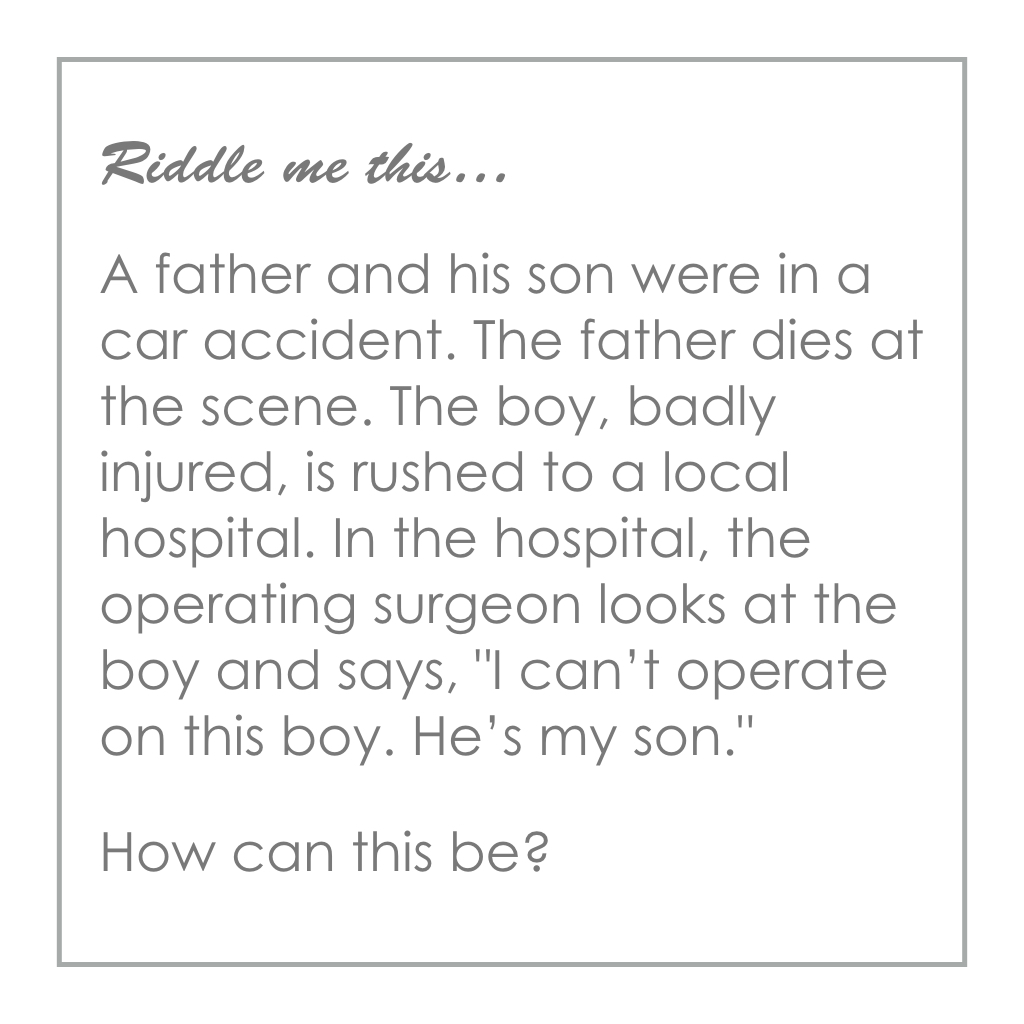

In particular, we want to talk about hidden biases and their danger. Below is a riddle that was posed on a recent episode of public radio show On Being. (It’s a thought-provoking show that dives into religion, poetry, art and science to explore the big questions of what it means to be human and to live purposefully.) This riddle illustrates the fact that, despite all our good intentions, our unconscious minds are often wired to harbor hidden biases.

SPOILER ALERT—THE ANSWER is that the surgeon is the boy’s mother.

If you didn’t get it right, don’t beat yourself up—80% of people don’t. If you’re one of the 20% who got it right—you’ve earned yourself a self-righteous pat on the back.

BIASES ARE HARDWIRED IN US

The moral of this story isn’t for us to feel guilty or ashamed, social psychologist Mahzarin Banaji explains on the show. It’s about recognizing the implicit biases hidden in our brains. Recognizing our biases doesn’t mean we are bad people—it’s recognizing that we are human.

‘We are at a point where our conscious minds are so ahead of where our less conscious minds are. Our conscious minds deeply believe in egalitarianism, in selecting people based on things called merit, on talent, and not based on the color of people’s skin, or their height, or whether they have hair on their head. And yet, we are doing that,’ says Dr. Banaji.

In light of the racial injustice and unrest that’s plagued America recently, Dr. Banaji’s words is particularly significant.

SHAME & GUILT ARE POWERFUL CHANGE AGENTS

Shame and guilt have their place—they help set our social standards for what’s acceptable and what’s not. It is good to shine a light on injustice and inequality, call out the unrepentant bigots—and let people know that hatred and bigotry is unacceptable.

In fact, here’s a helpful article on What You Can Do Right Now About Police Brutality. From racism to sexism, one of the first lines of combat is to force the hand of those in power—politicians, leaders of industry, celebrities—and shame or guilt or inspire them to change things from the top down. So please, go ahead, do that!

But that’s not enough.

WE GOTTA REALIZE THAT WE ARE ALL A BIT RACIST/SEXIST/BIGOTED

The root cause of systemic bias doesn’t just lie with the authorities or institutions. It also lies within us.

- Some “concerned citizen” called the police about the young black male pointing a pistol at random people at the recreation center. Tragically, the “threat” was a 12-year-old child with a toy gun.

- A “well-meaning” airline passenger heeded the TSA’s “See something, say something” plea and warned the crew about a suspicious passenger speaking Arabic and referencing “Allah.”

- A “sympathetic and thoughtful” boss decided not to give Mary the assignment in Shanghai because she has young children and he didn’t want to put on her the pressure of added responsibilities and a move overseas.

We all have been that someone at some point in our lives, whether we know it or not. I have called the local police to complain when a beat-up “junkie-looking” car was parked outside my house for several days, filled with clothes and stuff like someone’s living out of the car. When I walk alone late at night, I ignore anyone who tries to approach and keep my distance—I don’t stop to find out whether they mean harm or simply need directions or, God forbid, are in distress and need help. I don’t know whether my actions have kept me and my family safe—or whether I have added to the poisoned well of distrust and bias against the poor, the homeless, and the diverse people who roam the streets of San Francisco at night.

This is how bias is born and why it lingers. Because the same action and the emotions that trigger them can be legitimate and helpful in some situations—and yet be completely unwarranted and harmful in a different one. Dr. Banaji explains how our primitive brains have a tendency to associate “the Other” with a threat. Our default position is to fear and mistrust those who are different, those “not like us.”

“When our ancestors met someone who was different from them, their first thought was probably: Are they going to kill me before I can kill them?”

The problem is learning to counteract those impulses when they are no longer saving our lives but instead are causing harm.

SHAME & GUILT—A DOUBLE-EDGED SWORD

To create the widespread, sweeping change we all want so badly, we can’t just pin the blame on the few bad apples. We also have to look inside—focus on the majority of us well-meaning “good people,” and learn to recognize how and when good people can get blindsided by our implicit biases to cause harm and perpetuate inequalities.

That’s where shame and guilt can create obstacles in our struggle against inequality. Learning to differentiate “pragmatic good judgment” from “biased stereotyping” in our own actions is difficult when our reason gets tangled in an emotional stew of self-righteous indignation, shame and guilt. Once we’ve signed the petition at Change.org and taken a loud, impassioned public stance on social media against injustice—we feel vindicated, proven we’re on the side of “the good,” and we go back to our old lives, old habits and implicit biases, life goes on, and when the next tragedy happens, we are baffled and angry all over again as to why the positive change we all clamored for hasn’t happened.

That’s why Dr. Banaji titled her book, Blindspot: Hidden Biases of Good People,

‘The “good people” is extremely important to me. I do believe that we have changed over the course of our evolutionary history into becoming better and better people who have higher and higher standards for how we treat others. And so we are good. And we must recognize that, and yet, ask people the question, “Are you the good person you yourself want to be?” And the answer to that is no, you’re not. And that’s just a fact. And we need to deal with that if we want to be on the path of self-improvement.’

BE THE CHANGE YOU WANT TO SEE IN THE WORLD

Besides calling our politicians and making public protests against injustice and inequality, there are things we can do in our everyday lives to fight and counteract implicit bias. Looking at the learnings and best practices that Dr. Banaji created for businesses and institutions, here are some ideas and food for thought.

1. Cultivate A Colorfully Diverse Life

Look around you. The friends you hang out with. The kids your children play with regularly. How diverse is it? If it isn’t, start actively pursuing, nurturing and creating that diversity. No matter how good our intentions, implicit bias is born when we are not familiar with someone, when they feel “other” to us. We have to find ways to bridge the differences, to bring the “other” into our circle, our communities, our networks, so they stop being “other” and become part of a larger, connected “us.”

Our natural tendency and the path of least resistance is to bond with those “like us.” Just like it is easy for us to buy the cheapest things and eat processed food regardless of their impact on the environment, our society and our health. If we can make changes to our lifestyle, choosing to shop green, choosing to eat local, fair-trade and organic—don’t tell me it’s too hard to cultivate a life of diversity. We can do it if we choose to.

2. Set Boundaries on Our Positive Bias

Positive bias is about our natural desire to support those with whom we have a bond—like helping our neighbor’s child score an interview, giving a fellow alumnae the benefit of the doubt in a bid. Our motivation to help is not inherently bad—it’s human. But we need to be aware how these subtle advantages is what perpetuates the status quo and reduces the opportunities available to certain disadvantaged groups. It’s how “old boys’ networks” are created.

It’s unrealistic to think we can stop this completely—it’s part of what binds us to our communities and networks. But what we can do is set some reasonable boundaries on the nature and amount of help we give to special connections. And for every opportunity we give to a connection—let’s balance it by pro-actively finding an opportunity to open the door or mentor or sponsor someone from outside our circle—someone not like us. We will probably learn from this unexpected exchange as much as that other person!

3. Explore New Affiliations Beyond Race

Being tribal and wanting to bond with those “like us” is human. Rather than fight it, let’s be creative and explore ways to bond beyond race and class. Bonding by ethnic lines is easy because it’s often the most obvious. But when look beneath the color of our skin, there are many other shared values we can use to create authentic bonds and tribes. If you’re religious, join a racially diverse church. If you love your profession, get active in an industry network that is diverse in terms of race, gender and age. Love your sports team? Tailgate with fans from another class, another race.

YOUR THOUGHTS & IDEAS?

These are just thought-starters. If you have ideas, suggestions or comments for promoting equality and counteracting biases—overt and implicit—please share them with us. This works only if we all join the conversation and participate in the movement.

As a parting food for thought, here is another quote from Dr. Banaji.

‘I don’t want people to not learn from guilt and not learn from shame. I think those are powerful motives. They have made us, in large part, the more civilized people we are. But I do believe that, in our culture and in many cultures, we are at a point where our conscious minds are so ahead of our less conscious minds. We must recognize that, and yet, ask people the question, “Are you the good person you yourself want to be?” And the answer to that is no, you’re not. And that’s just a fact. And we need to deal with that if we want to be on the path of self-improvement.’

Photo by Kris Snibbe/Harvard Staff Photographer

is Richard Clarke Cabot Professor of Social Ethics in the department of psychology at Harvard University. She is the co-author of Blindspot: Hidden Biases of Good People, and co-founder of the implicit bias research organization Project Implicit.

MORE RESOURCES

Read the transcript or listen to On Being‘s full interview with Dr. Mahzarin Banaji.

White paper from EY and RBC on Outsmarting Our Brains and Overcoming Hidden Biases

Peering into Our Blind Spots—Interview with Dr. Banaji in the Harvard Gazette

What You Can Do Right Now About Police Brutality

What America Can Learn from Singapore About Racial Integration

Take the tests at Harvard’s Project Implicit to map out your own hidden biases.